Gregory Euclide

The Rain Brings Something Between Green and Passing, 2011

Acrylic, pencil, found foam, lichen, moss, photo transfer, pine, plastic, sage, sedum, sponge

29 x 23 x 8 inches

Gregory Euclide

Anywhere Kept The Frame Around Wanting, 2015

Acrylic, fern, goldenrod, sedum, moss, found foam, wood, pencil, pinecone, canvas, Eurocast

49 x 49 x 9 inches

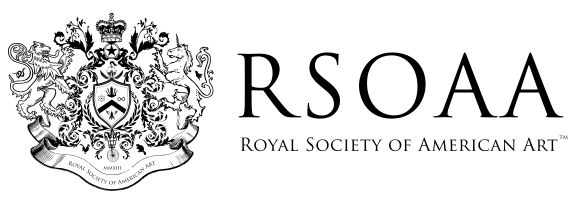

Linda Lauro-Lazin

When soft the western breezes blow, 2018

Digital monoprint on Rives BFK paper

18 x 13 inches

Linda Lauro-Lazin

I hear them singing as they shine, 2018

Digital monoprint on Rives BFK

13 x 23 inches

I am an artist and a technologist. I am developing a vernacular of digital mark making and abstraction that conflates traditional, analog and digital painting.

I began my current body of work by looking at satellite images of glaciers on my computer screen and selecting specific locations. I paint and layer the elements digitally: intuitively changing textures and colors and forming an abstract synthetic landscape. I bring an expertise in digital image processing to my studio practice and it informs my perception. I prefer to reveal the residue of the processes. Compression algorithms leave their artifacts. Physical blooms, cracks and brushstrokes echo natural phenomena. The synthetic mark is also my mark. Computers and surveillance equipment are in my studio toolkit alongside brushes and paint. This body of work has grown out of a culture of digital technology.

The work is about impermanence and loss: both personal and global. After researching archives, and making the digital paintings on screen, the imagery called for the kind of materiality only offered by physical paint. I approach painting as an amalgamation of digital and direct wet strokes into layered surfaces. The painted lines are like the contrails of my creative process over the terrain.

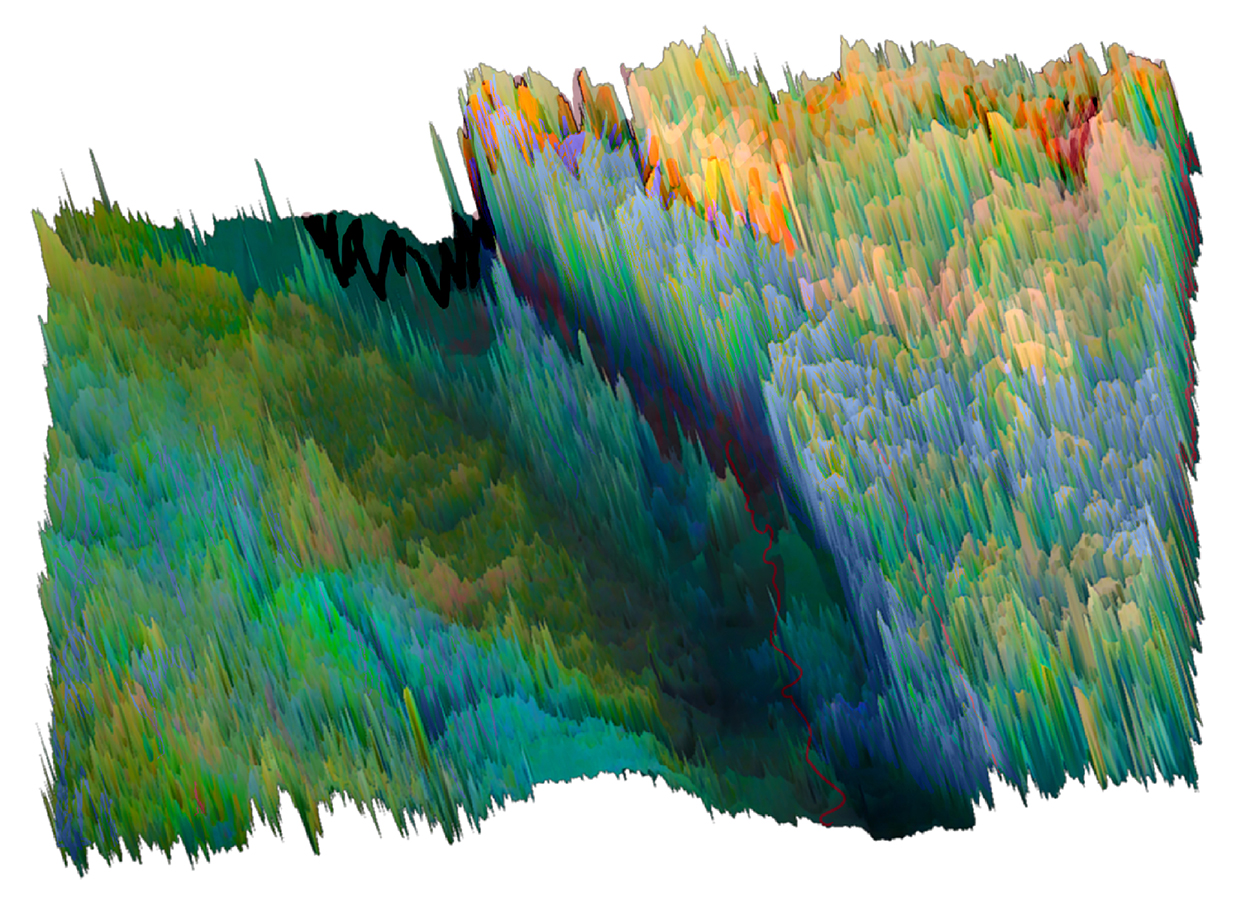

Cara Sullivan

Musk Thistle, 2017

Acrylic, spray paint and oil on hand-cut paper

13 x 9 inches

Cara Sullivan

Mexican Hat, 2019

Acrylic, spray paint and oil on hand-cut paper

13 x 9 inches

These works pay homage to the overgrowth: each painting features a different weed on a spray-painted surface with ornate profiles to reference the museum frame—the ultimate acknowledgement of beauty and value. More than a nod to the lowly weed, these paintings are for me a meditation on the irreverent, persistent nature and joy of rebellion. Selecting the weed over cultivated blooms is at odds with how we interact with the landscape. The weed is a metaphor for many things—a yearning to be wild: to live in a state of nature; for ideas popping into consciousness, unwilling to be censored; and for a revolt against false notions of beauty. This series of paintings feature typefaces from Heavy Metal, Punk and Rock ‘n’ Roll albums, connecting defiance across artforms. Here the underdog takes center stage, while in life our desire for perfection mows it down, poisons it, or pulls it out by its roots.

Basia Goszczynska

Fertile Fragility, 2020

Mixed media installation, dimensions variable

Basia Goszczynska

Equipose 8 (Fertile Fragility installation), 2020

Marine debris, wire, gauze, plaster, dimensions variable

In Fertile Fragility, I explore the precarious relationship between environmental conservation efforts and the desire for human flourishing, made possible by access to cheap reliable energy and materials. I created this exhibition in a state of heightened anxiety and vulnerability brought on by the global pandemic and exacerbated by tense political debate. The sculptures and installations in this exhibition, Scoured Equipose 1 – 11, are inspired by rock balancing, an art form that exemplifies a harmonious collaboration between humans and Nature. The materiality of this work marries the human with the non-human: earth-originating plaster is molded and scoured by hand and is juxtaposed by manmade foam, patinated by the elements. The plaster, meticulously molded and sanded, is a material often associated with the mending of broken bones and healing. The brain-like egg shapes symbolize the potent potential of new life, energy sources and ideas.

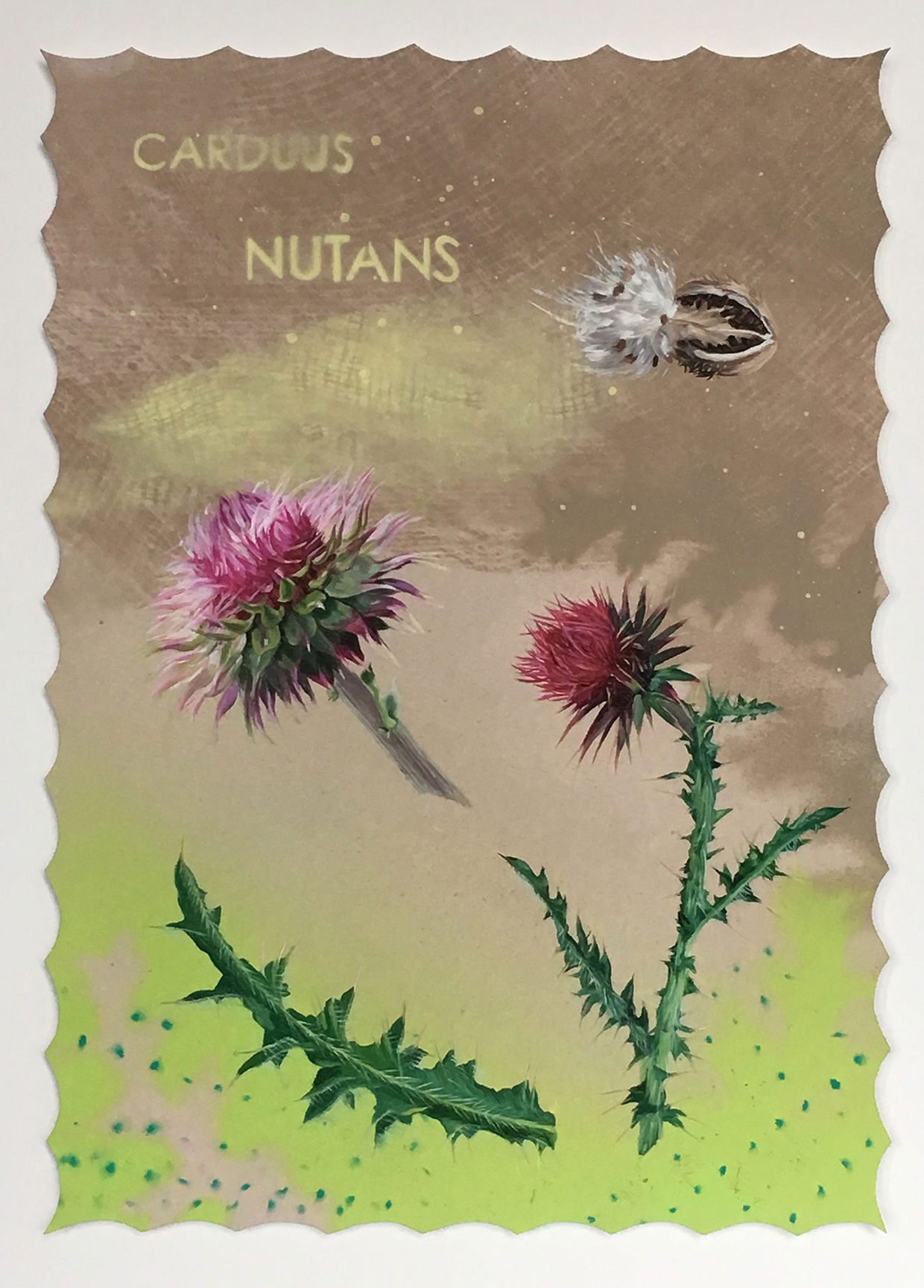

Sophia Heymans

Sleepover, 2019

Paper mâché, moss, prairie grass seeds, oil on canvas

60 x 50 inches

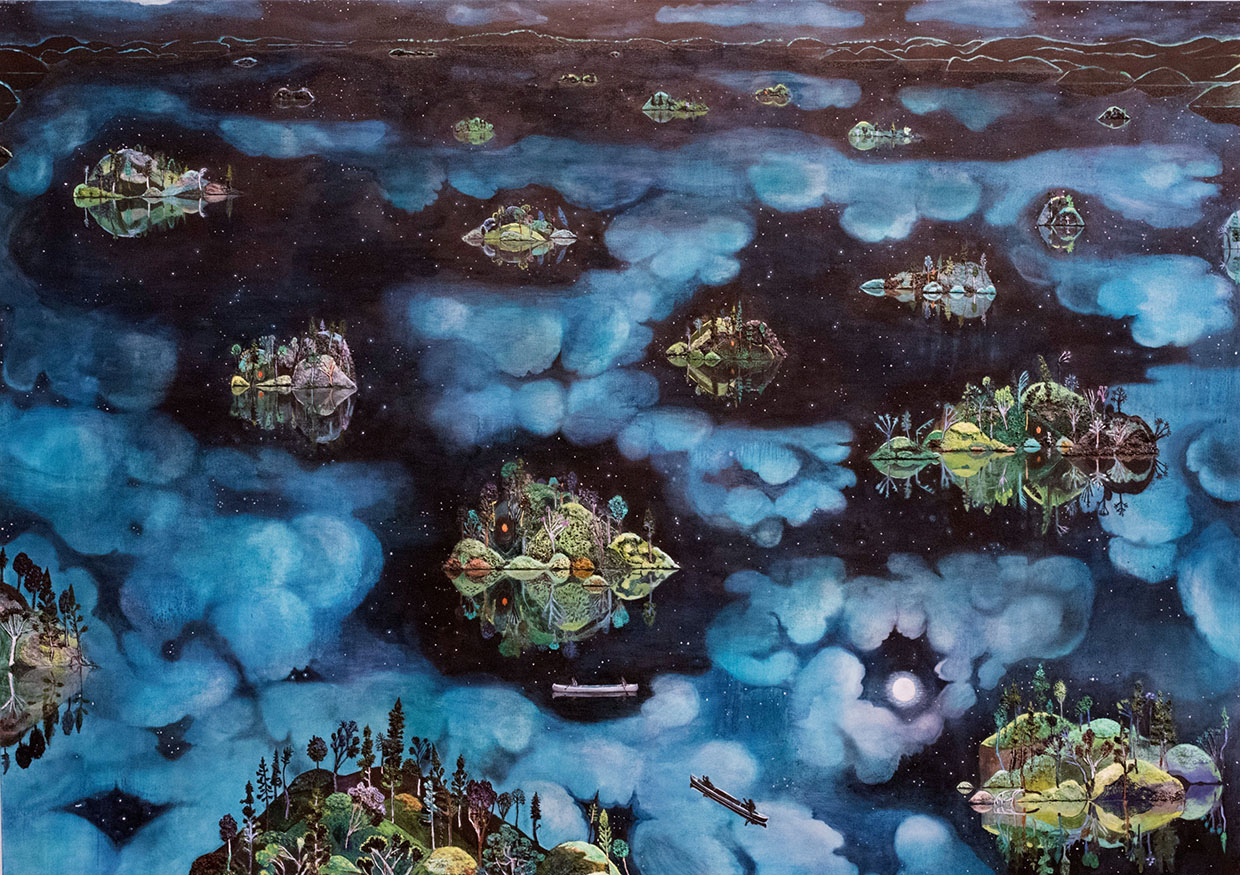

Sophia Heymans

On The Boundary, 2017

Paper mâché, moss, string, prairie grass seeds, oil on canvas

60 x 84 inches

The painted American landscape has long been used as a backdrop to tell tales of human trials and affairs. Countless artworks depict mans’ conquest and governance of wild lands, or else treat those domesticated worlds as places for our expansion and leisure. Even when seemingly depicting the grandeur of the wilderness, as with the Hudson River School Painters, the work still reeks of supremacy – peering ravenously down from a high rock at the wild young lands. There were less obvious postures of dominance, too; the Impressionists, for example, painted charming and peaceful outdoor scenes to inspire and comfort during times of industrialization and war, in the process reaffirming the misguided idea that nature is our inexhaustible refuge.

I do all I can to prevent my landscapes from becoming backdrops. I use an aerial perspective so that there is no clear foreground, no place for humans to claim dominance or steal the show. I don’t paint people atop the land, but paint them into it or beneath it. The humans are a mostly-veiled underpainting, entirely merged with the terrain.

Growing up, my sister and I spent most of our time outside. We explored every inch of our family farm, playing and imagining what took place on the land before we lived there. Were there any bloody battles? Did a mammoth ever sleep there, did a forest ever grow? I’d wonder how many stories were embedded into the land. How many people had loved it? I got to know that land so well that I began to feel like an extension of it, and it in turn became an extension of me: my body, my dreams, and emotions.

Instead of wondering if we belong on this land, I wonder if humans belong to this land. Does it hold something of us, a piece of us? For better or worse, we are here. But can we feel a physical connection to it, and even more so, does it still feel any connection to us? Does a river carry within in it any semblance of a man? Can a pond rest with the countenance of a sleeping girl? Do the rocks of the badlands hold a memory of the violence committed there? These paintings are not an attempt to personify the land, they are more of an exorcism. I am trying to find a wanting of our species within a landscape that we have felt separate from for centuries. Our western conception of nature as separate from us is unsustainable. I want to make permanent those fleeting feelings of connection. I paint humans as physically and psychologically intertwined with their environment so that you cannot differentiate between them. To destroy that land is to destroy ourselves.

Richard Barlow

Centograph I, 2020

Chalk on prepared blackboard paint

186 x 288 inches

Richard Barlow

Centograph II, 2020

Chalk on prepared blackboard paint

150 x 282 inches

My artistic practice is largely devoted to large scale, temporary and site-specific drawings of the natural world produced with chalk directly on gallery walls. These fragile drawings are erased at the end of their exhibition, a meditation on impermanence. This scene comes from photographs I took of Vroman’s Nose, a peak in the Catskills that is featured in Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire series, an anxious meditation on uncertainty from another perilous time in our country’s history. Unlike previous chalk drawings, I intend this piece to change over the course of the exhibition. I will return at intervals to alter the drawing to suggest wear and weathering in the lead-up to its eventual destruction.

Valery Hegarty

Picnic with Downy Woodpecker and Table with Chair and Pileated Woodpecker, 2015

(Sited at Olana–Frederic Church’s Estate)

Foamcore, canvas, paper-mache, acrylics, sand, feathers, wire, dimensions variable

Valery Hegarty

Autumn on the Wissahickon with Tree, 2010 (reinstalled 2015)

Paper, Tyvek, paint, glue, gel mediums, wood, foamcore, epoxy, wire, tape, sand, plastic, artificial leaves

108 x 60 x 28 inches

Valerie Hegarty is a Brooklyn-based artist who makes paintings, sculptures and installations that explore issues of memory, place and history. Hegarty relishes the materiality of her process and her works often incorporate a range of layered materials such as canvas, wood, Foamcore, paper-mache, and ceramics. Often starting with a personal inspiration, Hegarty seeks out poetic connections between her personal history, art history and current events. Although representational, Hegarty’s works contain surprising juxtapositions and uncanny transformations where materials and meanings are constantly shifting.

Hegarty’s large-scale installation work incorporates a process she calls “reverse archeology” in which layers of painted paper are adhered to the walls and floors of the gallery and then scraped back to create a material memory of a space.

Hegarty also constructs canvases and sculptures that replicate paintings and antiques from early American art history, only to falsify their ruination by devices associated with their historical significance.

Jude Griebel

Reanimator (Mice), 2014

Epoxy resin, wood, foam, plastic, textiles, oil paint

14.75 x 11.5 x 10 inches

Jude Griebel

Reanimator (Snails), 2014

Epoxy resin, wood, foam, plastic, textiles, oil paint

16 x 11.25 x 10 inches

The series of work Reanimator reflects my interest in applying didactic presentation traditionally equated with “truth”, such as models and dioramas, to alternative, psychological understandings of the body and nature. These works explore the dichotomous tendencies of human desire to romanticize and meld with, yet remain autonomous from the natural world. In Reanimator, this conflicted relationship is navigated through detailed sculptures that reference subject matter dealing with superstitious fears surrounding nature, personifying it as a force opposing humanity.

Taxidermy and museum displays typically portray fragmented and idealized vignettes of the natural world, re-composed and staged, despite being in a state of destruction. Animals and their environments become suspended in time through plastics and craft technologies for both didactic and trophy purposes. In Reanimator, I seek to subvert this tradition of display and conquest through tongue-in-cheek humor in which humans succumb to natural cycles of growth and decay. The work presents a metaphorical graveyard in which nature triumphs over humankind. Flowers blossom, insects and animals mate on headstones and hands surrendering to the soil become stages for proliferation. The sculptures function as hybrids between the nature vignette and vanitas tradition, in which the futility of our inevitable end is playfully countered with a sense of acceptance and becoming.

Refugia

November 13th – December 13th, 2020

Curated by Amelia Biewald

The Royal @ RSOAA is pleased to present, Refugia an exhibition of works by artists Richard Barlow, Gregory Euclide, Basia Goszczynska, Jude Griebel, Valerie Hegarty, Sophia Heymans, Linda Lauro-Lazin, and Cara Sullivan.

We welcome visitors to attend the opening reception of Refugia in person Friday, November 13th, 7 – 9pm. Attendees are invited to view the exhibition in groups no larger than 10 people. All current health guidelines must be followed, and masks must be worn.

Refugia: areas where special environmental circumstances have enabled a species or a community of species to survive after extinction in surrounding areas.

Our planet and surroundings have already been drastically altered by human intervention. What truly is untouched? Countless acts by the human species have effected and altered our environment, and our notion of the natural world reflects that. We have left very few areas undiscovered.

The ecological challenges we face are truly frightening. Nature was often seen purely as a commodity; something to dominate and to use for profit. We are interconnected with the natural world, and the forests, fields, mountains, and rivers are a community we all belong to and not a commodity we can exploit without consequence.

Thankfully this narrow view is changing and more and more humans are modeling their lives after ecological practices. The growing momentum for preservation is hope giving. These new perspectives on how we treat the Earth and Ourselves led me to take a closer look at how some contemporary artists are working with the concept of landscape.

“Landscape” is a term borrowed from art history — a painted picture of a view — a portion of the land that the eye can comprehend at a glance. How and where these artists choose to frame their view is an integral aspect of the works included in this exhibition. What is a landscape’s potential? These landscapes are anything but generic. We enter worlds of wonder, worlds where we can see the artists creatively building and making contemporaneous decisions as to how their “view” is constructed.

Their conversations with landscape intersect with culture, geographical differences, personal identities, politics, and histories. There also seems to be an emotional and spiritual relationship with the natural world. These aren’t your typical landscapes. Birds-eye views, erasing and reconstructing, technological reinforcements, digital production, and generally unique material use all contribute to complex worlds ready for interpretation.

Nature surrounds us, yet we can take it, and the mystery it harbors, for granted. These works give the viewer an intimate view of the artists’ personal relationship with Nature, and in doing so, help us recognize our natural world as a being — to restore, repair and respect. They beckon the viewers to question their way of “seeing” the natural world, and recognize the fundamental value of the environment.